By: AJ Witte

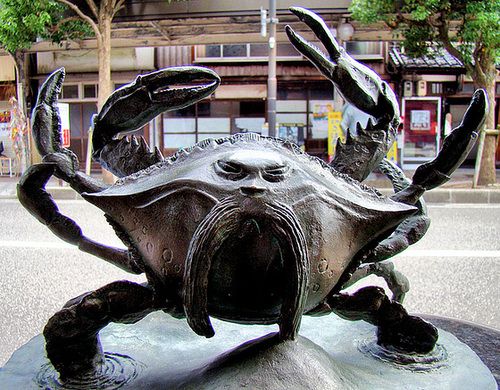

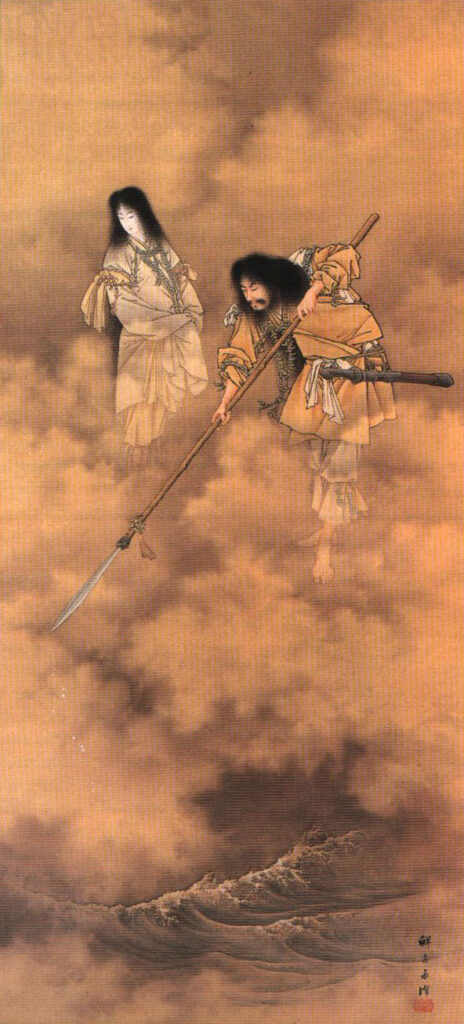

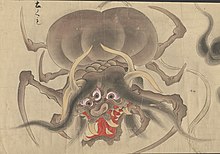

This past week we were tasked with reading several more Japanese stories, chief among: “The Tale of the Dirt Spider”. A story which revolves around the hero named Raiko, a hero who is based off of the real Kyoto bureaucrat who was the governor of several provinces near the capital of Japan. In this story Raiko and his retainer Tsuna find what is a monstrous spider who is eventually revealed to have eaten tens if not hundreds of Japan’s people. They eventually kill the spider uttering the names of their gods and receive land and recognition for their valor and accomplishment. This reading can be taken a few different ways, but as the textbook suggests, the great spider is meant to represent those who oppose the throne. The word for dust spider refers to such: “The word Tsuchigumo (eart, or dirt,spider ) appears in ancient texts like Kojiki (Record of Ancient Matters, 712), where it refers to rebels afgaisnt the throne, and it probably derives from tsughigomori (dirt dweller), in reference to the pit housing in which those rebels may have lived” (Keller and Shirane 23). The dust spider being a metaphor for those who are outsiders is a very interesting one as during this period of Japanese history we see quite a lot of strife and rebellion. Whether this be from the rebellion of Taira no Masakado in 939 to the growing power of the warrior class, the samurai. We see a large shift of power away from the traditional norms and status quo of the emperor to these outsider influences and powers. I believe that the uttering of the traditional gods of Amaterasu and Sho Hachiman, “It wa strong – strong enough to move boulders and it tried to wound them. Raiko prayed to Amaterasu and Sho Hachiman, ‘Out country is a divine land protected by the gods, and the emperor rules through his ministers. I am his vassal and descended from kings, born into a house blessed with the imperial lineage,” (29). To me this declaration reads as a return to form. A renewal of the old ways and to a form of power that is no seemingly drifting away. It can almost be read as a kind of propaganda piece against the changing times. It is interesting to me that in every culture we can see this kind of nationalistic story telling from Shogunate Japan all the way to modern day United States.

Sources:

“The Tale of the Dirt Spider.” In Monsters, Animals, and Other Worlds: A Collection of Short Medieval Japanese Tales, edited by Keller Kimbrough and Haruo Shirane, 23-30. Translations from the Asian Classics. New York: Columbia Univ. Press 2018.